The early 20th century was a time of experimentation for crime photographers. Although offenders were the original subjects of crime photography, police photographers soon began to document crime scenes as well as perpetrators. Advances in film and camera technology – including smaller and more portable cameras – meant that police photographers were able to travel to different locations to capture images of crime scenes as well as criminals.

Years of creative crime-scene photography

Technology moved quickly and for many years crime-scene photography was not standardised and lacked a set methodology. This allowed for more room for creative interpretation and variance of style, resulting in the wide array of almost artistic photographs within the crime-scene photographic archive.

Snapshots of the aftermath

Police photographers attended crime scenes, taking snapshots of the scene and the aftermath of the crime. Before the introduction of acetate film, these photographs were taken using glass plate negatives. The museum has over 500 of these striking glass plate negatives in our crime-scene photography archive. The events behind many of these photographs are still a mystery, but recent discoveries have uncovered the stories behind a handful of cases.

Left lying in a laneway

This photograph depicts the crime scene from a major incident in Clifton Hill, 1933. On a spring night in 1933 a large brawl broke out in Clifton Hill. Police suspected it was a clash between two rival street gangs, then known as 'pushes'.

The fight erupted when a young man and his girlfriend were attacked by members of a rival gang. Reinforcements from both pushes arrived, pulling pickets from fences to use as weapons.

During the brawl 24-year-old Henry Daley was brutally struck in the head and left lying in a laneway.

'Manslaughter by persons unknown'

When police arrived they found him unconscious, surrounded by bloodstained pickets. He was admitted to hospital with a fractured skull but died days later. Several men were arrested for their involvement in the fight.

Prosecutors later alleged the brawlers were from 'Reilleys Push'. Police suspected the push members knew the identity of Daley’s murderer but were refusing to give him up. A month later, Daley's killer was still unknown and the coroner recorded a finding of 'manslaughter by persons unknown'.

Detective work

The Clifton Hill brawl was investigated by one of Melbourne’s most famous sleuths, Detective Sickerdick. In the early 20th century, the detective – a new breed of crime fighter – gripped popular imagination. The covert and secretive nature of their methods and the esteem attached to their position had a seductive pull for novelists, film-makers and journalists.

Melbourne media imparted celebrity status on some real-life detectives, depicting them in newspapers, radio shows and magazines as local versions of Sherlock Holmes or Philip Marlowe. The cases of men like Detective John Christie, Reg Henderson and FJ Piggott were eagerly followed by the members of the public with a thirst for true stories of mystery, intrigue and Melbourne's underworld.

Detective Sickerdick was one of a group of detectives working in Melbourne in the 1930s. Sickerdick assisted in the investigation of the Clifton Hill Brawl, and suspected the involvement of the Reilleys Push.

Shot dead in his shop

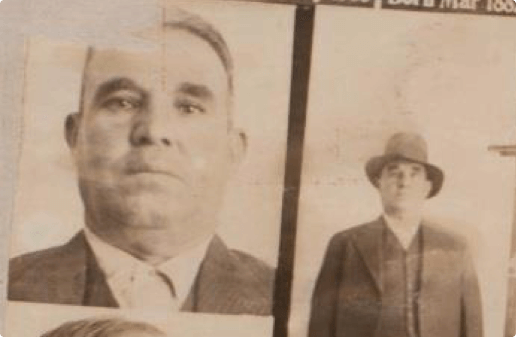

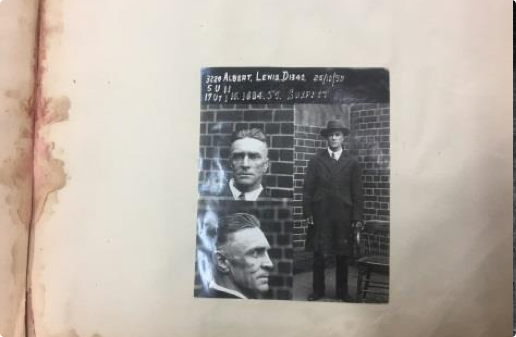

In late October 1933 pawnbroker Maurice Langley was shot dead in his Elizabeth St shop by two armed assailants, while his brother, sister-in-law and friend lunched in the other room.

Langley had been enjoying a meal in a room adjacent to his Elizabeth St shopfront when he heard someone enter the shop and went to investigate. Moments later, shots were fired. Langley's brother rushed in and witnessed him staggering backwards. Before dying he gasped ‘he shot me’, pointing to two men standing before him. A struggle erupted and one man was captured but the other fled. He was later identified as Albert Lewis.

Captured man

The captured man was 50-year-old Robert Ernest von Geyer. He claimed he had simply entered the shop to claim a £5 debt from Langley, who had drawn a gun on him and shot himself accidentally. The truth was a little less simple. Witnesses said the men also threatened Langley’s brother, saying ‘We will get you yet!’

Was it a gangster-style assassination, or a fight gone wrong?

Organised crime

During questioning von Geyer allegedly attempted to bribe a young constable. Von Geyer requested the young man set him free, saying it would be ‘worth £50 to you... you can say I got away’.

Von Geyer suggested that Henry Stokes, the notorious underworld figure, would provide the cash. Henry Stokes was an associate of Squizzy Taylor and a key figure in Melbourne’s organised crime network. This underworld connection seemed to give von Geyer confidence: he declared ‘You have nothing on me. I’ll be having my Christmas dinner at home’.

He was almost right. Although he was eventually charged with manslaughter, he was freed two years later. Was he working for Henry Stokes's gang? Perhaps underworld connections had led to Langley's death? Von Geyer had, after all, suggested the death was the result of an argument over an unpaid debt.

The payroll killings

Frederick William Sherry was shot in the gutter during a dramatic armed robbery in Clifton Hill in September, 1938. It was the second armed robbery to which he and his brother had fallen victim. The brothers owned a shoe factory and made regular trips to the bank with the company payroll. It was on one of these trips that the first hold up occurred. Although they escaped unscathed, the brothers then decided to make future payroll trips accompanied by police escort. Months later, on their first trip without a police escort, they were again confronted by masked men. William Sherry escaped with 50 pounds as a diversion, so the driver could make a getaway with the remainder of the cash. As Sherry fled he was shot dead by one of the masked men, who made their getaway in a car that was found burned and abandoned. The masked men were soon discovered to be Selwyn Wallace and Herbert Jenner. Both received the death penalty, but their sentences were reduced to life in prison.

The first hold up

Six months earlier, William Sherry and his brother Clarence had been returning from a bank in Northcote when they were held at gunpoint by two masked men. Shots were fired and the brothers narrowly escaped by ducking down and driving quickly to Collingwood police station. Although the brothers escaped, they were convinced the bandits would strike again. It was after this that they began to take their payroll trips with a police escort. It was several months until they felt safe enough to go alone.

Known accomplices

Selwyn Wallace had been spotted driving the getaway car near the scene of the crime. He agreed to make a statement about the robbery, but insisted he had not shot Sherry. Wallace refused to name his partner saying an ‘unknown man’ had offered him 100 pounds to drive a getaway car. He insisted he “never squealed on a pal” and was happy “taking the rap for the holdup”. Later, when he realised he could be charged with murder and executed, he named Herbert Jenner as the man who had fired the gun. He gave police Jenner’s whereabouts, where they found a box of bullets. Although both men had denied knowing each other, close analysis of their prison records suggests the two men were familiar. Both served almost identical sentences at the same prisons, over a period of several years.

“photography, like murder, interrupts life…” L Sante

Carefully photographing each crime scene, 1930s police photographers took snapshots of times and places where lives unravelled. Although some photographs have been separated from their stories forever, the images still transport us back to the scene.

These photographs still bear witness to the terrible aftermath of crime, 90 years on.

Updated